Students become teachers – Capacity Building in Jordan | Interview with Enas Qasem and Ahmed Hariri

- Home

- Students become teachers – Capacity Building in Jordan | Interview with Enas Qasem and Ahmed Hariri

Founded in 2016 with the support of ArcHerNet, the master’s programme “Architectural Conservation” at the German Jordanian University provides both Jordanian and refugee students with an academic qualification in the fields of building archaeology, heritage conservation and cultural preservation. Two former students, Enas Qasem and Ahmed Hariri became trainers in the training course on the Post-Conflict Recovery of Cultural Heritage initiated in the framework of “Stunde Null/ Zero Hour” by the Department of Building Archaeology and Built Heritage Conservation at the Technical University of Berlin (TU). In this interview they talk about their experiences and their perception of cultural heritage in the area.

Could you tell us a bit about the master’s programme “Architectural Conservation”?

Enas: We had several theoretical courses with our regular teacher at the German Jordanian University and practical training for a week or two each semester with the visiting lecturers. We had various courses on theory, manual and digital documentation and photogrammetry. They were followed by courses on pathology diagnosis and damage assessment as well as lectures on tourism management and site management. The whole programme was complemented by intensive workshops with the lecturers and professors that came from Germany.

What was the most useful thing you learnt?

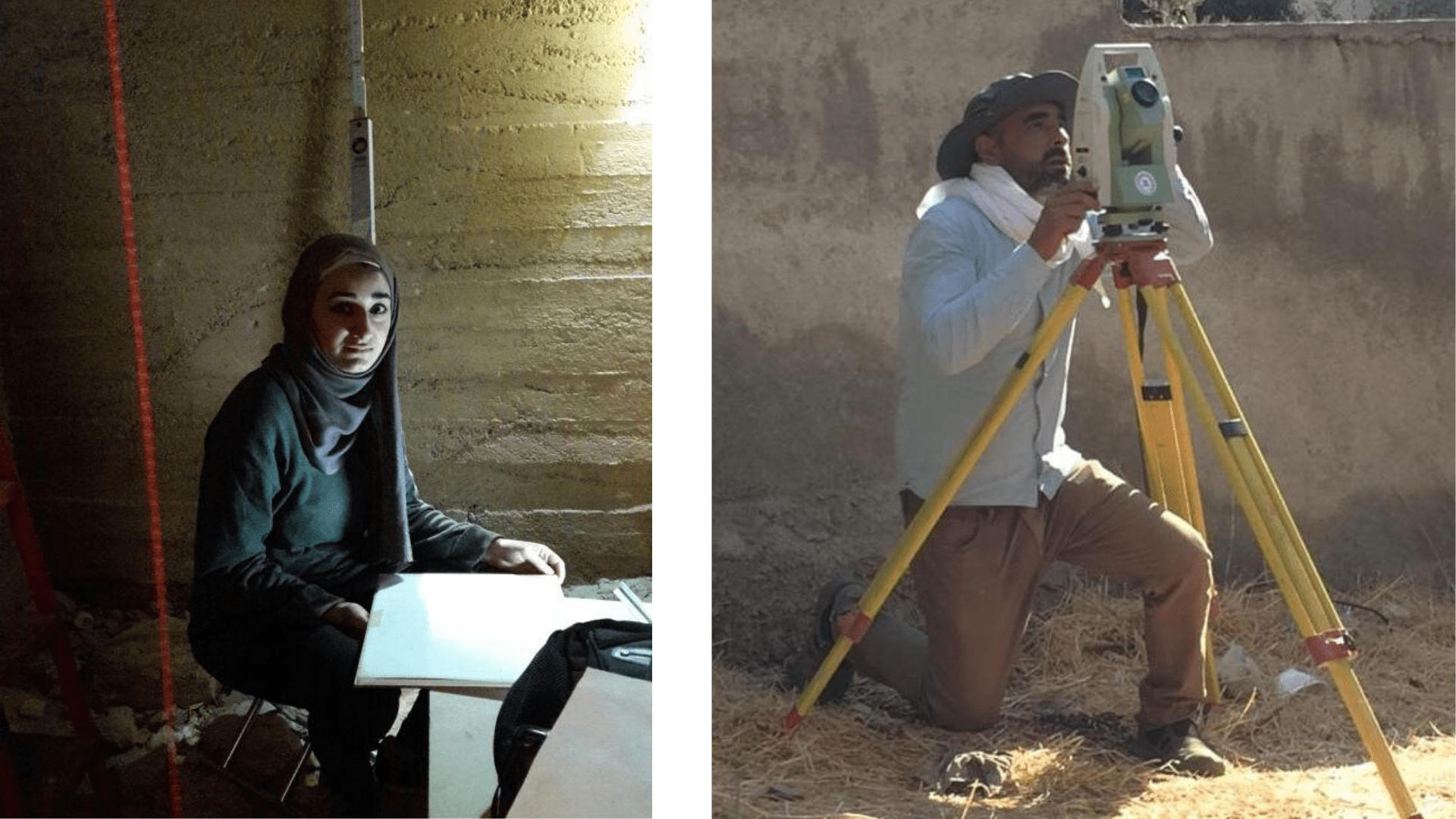

Ahmed: It was the theory and the practice. I come from a civil engineering background. Learning the principles of architectural and cultural conservation was very useful. During the conservation workshops I was in charge of the total station, an electronic instrument used for surveying. I already had experience, since I dealt with this instrument as an engineer. But the way we used it within the field of architectural conservation is different. Processing the photogrammetric data and getting very precise results is something I will be taking with me, for sure.

The practical part, the field work, can be adventurous at times. How did you experience it?

Enas: Yes, field work could be quite exciting sometimes (laughs). During our work we had to climb up to finish our documentation of the heritage site. Unfortunately it wasn’t easy to reach everything. In the beginning we were pretty anxious about making the climb. But we were laughing a lot while we were trying. One time we worked in Jerash and during the excavation it was very hot and sunny and we were 5m deep in the ground, working on the documentation of the architectural fragments carried out in the excavation. That was quite adventurous. I like to think back to that time.

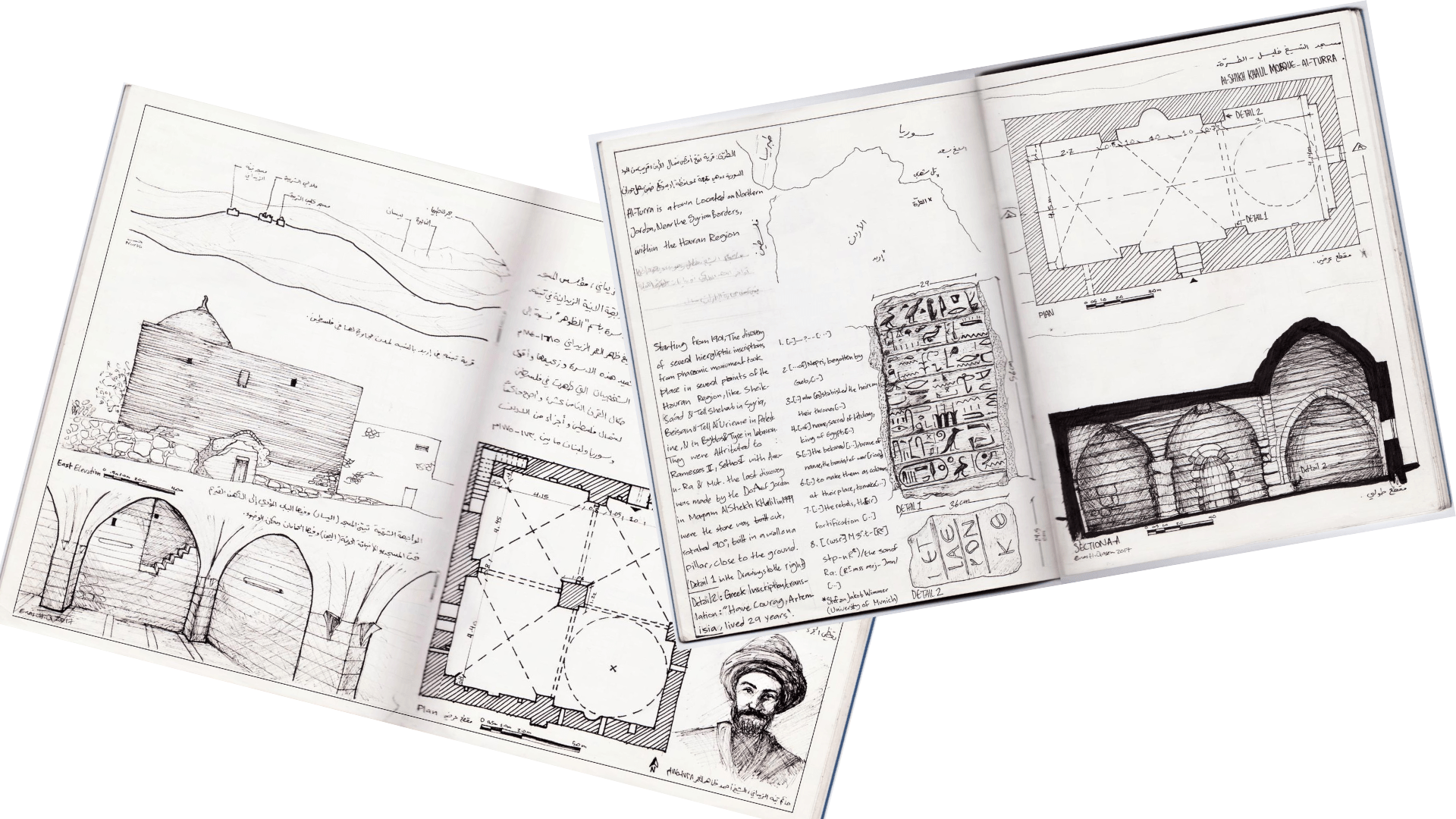

In one semester, every Saturday we had a site visit to a remote old mosque to document it. We tried to find it with our map and kept asking around. Sometimes we would find the mosque we were looking for, other times we would find a completely reconstructed one or a completely new one, and sometimes we would find nothing! One time we went to an old mosque in a distant village and a group of little children gathered, and started to make noises when we went to the minaret. They were quite naughty (laughing).

Ahmed: Yes, the whole experience was fun. But I liked our visit to Umm Qais in 2018. I did not expect it to be so close to the Sea of Galilee. It was the first time I saw the Sea of Galilee. I was astonished by the scenery and the site. This is something I will never forget.

Did the international aspect influence your studies?

Enas: We had had multicultural experiences before. We had Syrian, Jordanian and Iraqi students in the programme. Starting to work in the field of cultural heritage, we began to talk and it became clear that the students felt a love for their heritage. We got to understand the different perspectives of our colleagues and their heritage and talked about past experiences in their countries. I was curious what they were like and I learnt a lot from them.

You have different nationalities but also a common heritage. Did that play a role during your studies?

Ahmed: I graduated in Syria in 2009. At that time, we studied with students from different countries: Jordan, Sudan, Egypt, Iraq, Tunisia, Algeria… The difference is maybe how the people value their heritage. It was interesting for me to see how they take care of their heritage. We did not deal with this topic a lot during my studies in Syria. So the whole approach was new to me.

Enas: When you learn about stone conservation, for example, we use the same techniques in Syria or in Lebanon. Maybe in Iraq it is a little bit different because of the mudbrick architecture, but of course the basis and the techniques are the same. What we learned is applicable everywhere.

How did you feel about the work with the German trainers?

Enas: During the training courses we had lots of information in a very short time. It was nurturing for the mind. We had a lot of theoretical case studies with our resident teachers. For example in the pathology course we had a lot of case studies from around the region, but not many site visits. That was covered during training by the visiting teachers. I think the courses with the German and Jordanian teachers complimented each other.

Now you are trainers yourselves. How do you feel about that?

Enas: I did not expect to become a trainer so soon but when Mada Saleh from the Technical University in Berlin and Muhsen AlBawab contacted me and told me they were looking for a trainer, of course I accepted immediately. I felt really honoured and did not think that I could do it, but we worked really hard and thankfully we had this opportunity.

Ahmed: From the first workshop as students with Claudia Winterstein and Prof. Thekla Schulz-Brize I liked the use of the total station. This was my game! I demonstrated my interest and that I had the preliminary knowledge needed to use the instrument. One of the advantages to be a civil engineer is to be familiar with the survey techniques. So I tried to do as much work as possible at the total station to learn more about the use of this tool within the field of architectural conservation. Then I was approached by Mada Saleh. She told me they needed somebody in the training course of the TU in Jordan. So I said yes. It was an honour for me and I enjoyed it.

What did you teach?

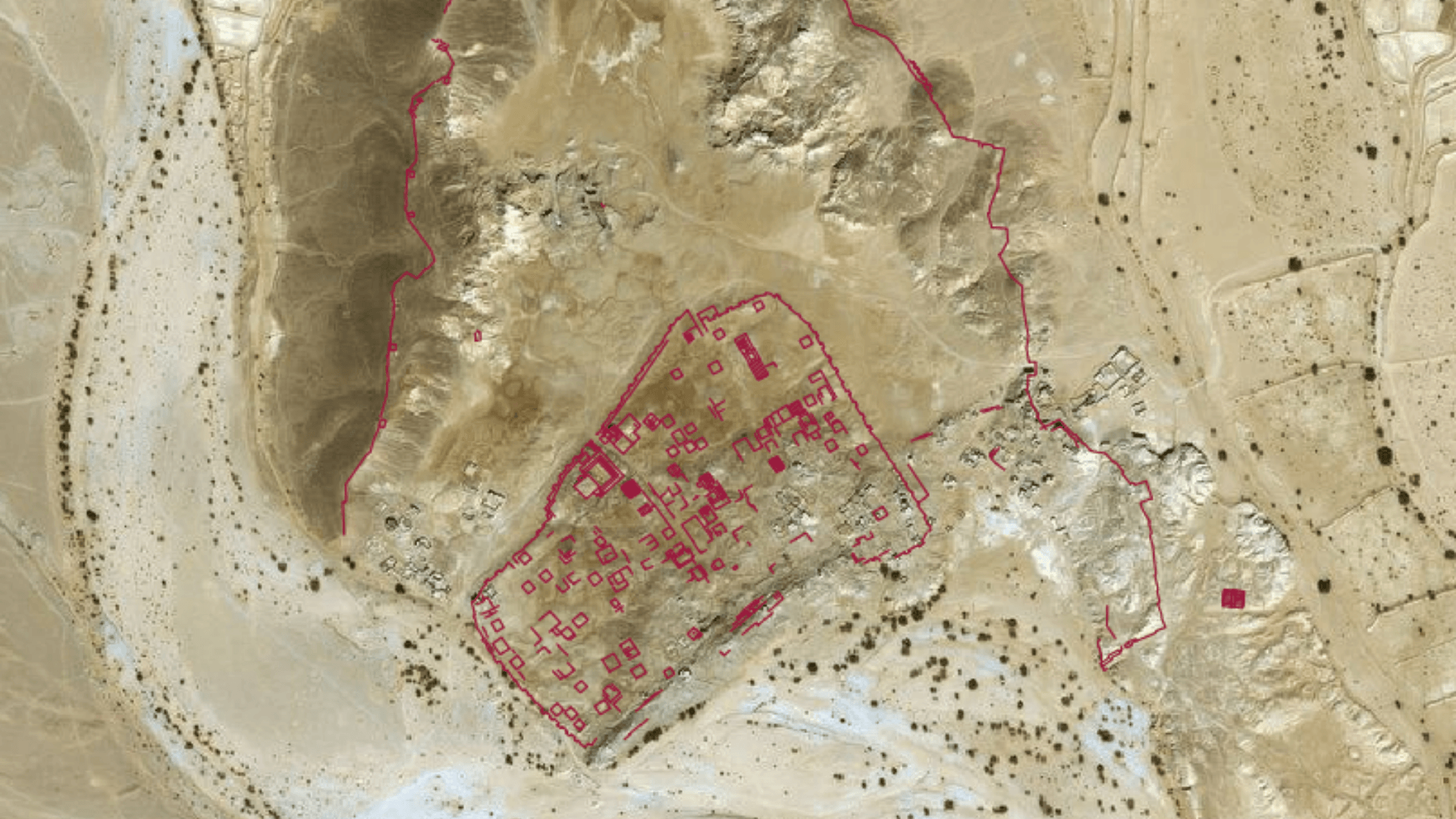

Enas: I taught cultural site management. We had a theoretical part and practical training. We did a site management plan for a site in Amman (Qasr al-Nwaijis) and also had a site visit to Iraq al Amir, which is a Hellenistic monument in Amman. I had worked for the Department of Antiquities (DoA) before, so I knew about the sites and I took the students there to discuss the DoA management of the site Iraq al Amir.

Ahmed: We had a theoretical part and fieldwork. For the first part, I supported the students who didn’t have strong language skills and explained the technical terms in Arabic. For the field documentation, my advantage was that I had worked with the total station and knew the terminology. So my job was to help them to master this tool.

Was it easy?

Enas: It was challenging. I had to prepare a lot each day before every lesson or site visit, but I liked it a lot. Now, I am thinking about working in academia and continuing to teach. It was a great experience! The trainees were about the same age as I, so we were rather like friends. It was fun.

Ahmed: For me it was challenging, too. It was my first time teaching on that level. I had past experience teaching English and mathematics to students. The teaching itself was not a big problem, but to prepare something that you do not have that much experience in, was. But in the end it was a challenge and I had to do it. It was an enjoyable task. I realised how much I had l learned and was happy to pass on the knowledge to a generation that was not much younger than me.

Did either your studies or your teaching change your perspective on cultural heritage?

Enas: I worked with the Department of Antiquity before so I already had a connection to cultural heritage. However, it is a little bit different than before. Of course, we gained a lot of new experience and perspectives towards cultural heritage during our studies, but from a practical or administrative point of view it is quite different. There are a lot of laws and restrictions you have to take into account during your work. Budgeting, administration and gaining access to information became much more important in real life than it was as a student.

Ahmed: To see the destruction of Syrian cultural heritage in the media 2015-16 and 2014 in the case of Palmyra left a long-lasting impression on me. As an engineer I worked in Tadmoor near Palmyra. I visited Palmyra on a monthly basis. So I had a special relation to this world heritage site. I really liked it, but at that time as a visitor not as a specialist. It broke my heart to see its destruction from afar. I had no idea at that time that I would one day be a part of a group that would be committed to the protection of cultural heritage. These images were one of the reasons why I applied for the Master’s Programme “Architectural Conservation”.

Do you plan in the future to focus on something in particular?

Enas: In my Master’s thesis I tried to focus on some technical issues and combining archaeology with my knowledge of architecture. I focussed on protective shelters for mosaic pavements with several case studies in Jordan. In the future, one option for me would be to do research on how urban infrastructure is affecting the preservation of heritage assets. I also have a personal interest in media and filmmaking. I was thinking about studying how media influences the interpretation of heritage.

Ahmed: My Master’s was on mausoleums in north and central Jordan. This is related to monuments in Syria and Palestine. There are similar examples of monuments in Palmyra, too. What I would like to write about in the future, are practical ways to preserve the monuments in Palmyra.

Now that you have taken part in the study programme and are trainers yourselves, would you consider yourselves advocates of protecting cultural heritage?

Ahmed: Looking now at cultural heritage with the eye of a specialist, it definitely influences my whole thinking and perception. It is easier to visit the monument and just pass by and that’s it, but now when I pass by a badly preserved monument, I feel sorry for it. I have developed a feeling towards these monuments and I do feel more responsible now to advocate our cultural heritage and preserve it. Being part of this programme was an advantage. It is quite new in the region. Here we value the heritage from the perspective of tourism. Having this knowledge now, my views have completely changed.

Enas: Now that I have the knowledge, I feel that I have the responsibility to spread it and defend our cultural heritage. But I still have a lot to learn. Before we share we have to make sure that we have the full picture. I would like everyone to look at the history and our heritage not as a detached aspect of life. If we are attached to our history it becomes much easier to build our future.

Thank you!

The interview was conducted via skype by Eva Götting and Dr. Nathalie Kallas.

Read more:

Archaeological Heritage Network is made possible by many national and international partners. The Federal Foreign Office and the Gerda Henkel Foundation supports the network.